“I want my teachers to make me feel safe in our classes and on school grounds.” (Middle School student to group of scholars and doctoral students during a conference in 2019)

“I’m afraid to say anything to my colleagues because of what they may think of me.” (A teacher’s comment to me as we listened to the student). My response to the teacher: “You should quit the profession. If we do not protect our students in our classrooms and outside of it to colleagues, then we are a part of the problem. Quit.”

A keen departure from the kind of blog we typically write for Today Parenting, this blog emerges from months of research, reflection, teacher and student comments, concerns, and the increasingly critical divide between parents and teachers—a divide that is exponentially expanding every day. Add in community input, social and political input, what emerges is decidedly not always clear, proactive actions and decisions, regarding the purpose of K-12 education and its foundation: the curricula, the intellectual and social maturation of our children. Unfortunately, what has and continues to emerge are untenable environments—environments being less conducive to learning, exploration, critical thinking, and life-long skills required in both private and public life—skills which both parents and classroom teachers foment and scaffold for college and workforce.

Can we “shift gears and focus to address these ever-threatening issues before we risk losing any possibility to address it for our kids?” And if we dare to think we can turn the situation around—what are our options to address this impasse—an impasse that at times appears impossible to rethink, and thereby, impossible to reconstruct for our kids’ future?

To begin, we as parents and grandparents, veteran, new, and preservice teachers, and administrators need to take a look back first, to remember where we and our schools once were in order to see clearly without blinders our present state. Secondly, we need to process, reflect, and think through what we must do now to reconstruct and rebuild before time literally runs out—not only for us—but time running out for our children and their children to come. The situation is just this dire.

“We never thought about guns and lockdowns [in school].” US Rep. Jasmine Crockett (TX), re the Allen, TX Premier Outlet shooting, MSNBC American Voices, 8 May 2023

Remember?

- Fire Drills: This ubiquitous precaution throughout the nation’s schools, were always unexpected and orderly. Teachers were in complete control and students were happy to go outside. As a high school teacher, I would even tell my students, take your notebooks so that we can continue our work during the drill. Yes, a bit different—well, a lot different, but my students were great sports about it, and we continued learning.

- Duck and Cover Drills: The screeching siren-horns, alerting students, and teachers to hunker down immediately under tables and desks, using their hands and arms to protect their heads and necks—without allowing them even a second to think and ask why. This alert continued for some time in an effort to protect school children, teachers, and staff from potential atomic attacks, from the 1950s well into the 1960s (in Minnesota—1950s-1974).

Not any of these drills frightened us, not even the Duck and Drills because it all seemed so distant. In addition, our teachers and parents made us feel safe. The school’s administration further bolstered this sense of “safe space,” as well.

In contrast, however, where are we now? As time and events have moved forward, our schools’ being the “safe space” metaphor and symbol have changed to include not only the physical, outside occurrences that happen all-too frequently now around our country—elementary-college—but also into individual classrooms. These increased safety measures emerged in the wake of Parkland FL, Newton CT, and Virginia Tech.

Memory: I have been in more schools than I can remember. However, one school and moment in time continues in so many ways to haunt me because, like US Rep. Crockett, I had never envisioned school in this manner: As I walked into the school, the very first image was of two police officers seated at a table. On the table were wands that I’d seen and experienced in airports, when I went to Capitol Hill, and the White House at the entrances. In addition to the wands, was the walk-through metal detector. And if that was a shock and an awakening, within minutes I witnessed a student who had an umbrella in a backpack summarily escorted out of the building by one of these officers. All, within my first 15 mins and all occurring in the entry.

Think about and process the following. Not one single student in the United States of America today is unfamiliar with the following list, its implications, and, tragically, the potential consequences.

Present:

- Remain/Shelter in Place: keeping students, teachers, staff, and administrators in the one place where they are presently located, locking the doors.

- Lockdown: similar to shelter in place; however, Lockdown also entails eminent danger from the outside that requires all external doors/entrances to be locked. No one goes in or out until authorities arrive. Lockdown most often occurs when the danger involves a shooter, or person actively seeking to harm the students, faculty, staff, and administration.

- Early Dismissal: can occur because of weather or city/state/national emergency, and at present, when bomb or other dangerous threats are made.

- Active Shooter School Incident Guide: Many schools have access to such guides, for example, Colorado School Safety Resource Center provides this document: Best Practice Considerations for Armed Assailant Drills in Schools.

- And yes, the “ubiquitous” fire drill: practiced evacuation along the nearest routes with teachers’ taking attendance once students are safely out of the building.

During a lockdown, all inside the school must adhere to the following:

- Gather students and lock the door.

- Evacuate restrooms; however, if a student or teacher cannot exit the restroom, determine some way to secure the door.

- Turn off all lights, cover windows.

- No walking; stay close to the floor.

- Make no sounds.

- Teachers make sure all students accounted for in the class.

- Cell phones: don’t use unless trying to call for help. Silence all phones or put on vibrate.

Ironically, GenZ has never experienced the safe and secure school environments as their parents and grandparents—a complete unknown. It is within this new physical and emotional construct that students endeavour to learn, teachers strive to teach and nurture learning, as administrators and staff work to maintain and sustain order, continuity, and safety for all. All the while, parents endeavour to know and trust that the schools “work,” as they have in the past, educating their children safely to and from home and inside school and classrooms every day.

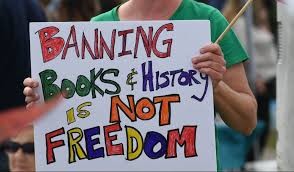

Juxtaposed to the physical, emotional, and psychological threats surrounding our children daily is the accelerated impact of book challenges, bans, and sometimes verbal confrontations. Of course, such challenges are not new. However, in the past, teachers, parents, and administrators collaborated to arrive at tenable solutions, especially in ELA classrooms. Literally, during the 1980s and until recently, these groups coming together to explore, seek out experts in the field to guide and advise, as well as listening to the students themselves was the norm. The result, generally would be a created process by which a designated committee would review challenged texts, discuss, seek additional information or guidance, if they deemed it necessary, and arrive at decisions and alternatives. Administrators, teachers, and parents most often comprised the review committee. In addition, the committee and/or teachers often sought out experts to aid, guide, and review.

Personally, I have attended many of these meetings at the request of the administration, teachers, and/or parents. Without exception, what remained a constant—an important constant—was the town meeting with the board, parents, teachers, and students. Time was always allotted for all voices to be heard; a Q&A would generally follow. The Q&A is an important time because, in my experiences, all sides have time to make a point or to drill more deeply into an area that, as the objective specialist from the outside, I would be able to respond, not only relying on the challenged text(s) alone, but also on research, and citing other schools’ experiences and approaches around the country. Even in the most trying times, and there have been many, I can honestly say that at the end of the day, everyone felt they’d been heard and seen. This is not to say every text was saved; rather, I recount these past and contemporary experiences to illustrate that in almost every case when the adults afforded students to speak up and participate, all of us benefited from privileging their voices and perspectives.

“I chose this book because I had read another one from this author, and that book kinda moved me and gave me a different understanding of kinda how life was for other people. So, when I saw this book, I was curious about it. This book shows me how much people can be oblivious about banned books. Like if you stop people on the streets and ask them about what books are banned and which authors wrote the books that are banned? They would have no idea. I’m trying to understand how a book like this can be banned from the school environment? (8th grader Looking for Alaska—2nd read)

But, again, this generation of students, an increasing number, may never have the opportunity to read, explore, weigh, and reflect on a growing number of texts—fiction and non-fiction—not because the challenged and banned books are immediate detriments to who they are as individuals, or to their individual psyches. No, the targeted texts are challenged because in so many ways they foment inquiry— inquiry that may or may not align with what others believe and/or champion. In addition, those who challenge or ban the texts are not always parents. Today, so many of the challengers are outside of the immediate family: community, local, state, and federal government, a variety of interest groups—each with its own agenda—none of which considers fully the purpose and import of the classroom—and in relation to this blog, the English language arts classroom.

“I’d read this book when I was younger. When I saw it on the list, I decided to read again. I have to confess; I really did not remember it. But now that I’m a couple of years older, and I’ve gone through more things, I’m able to understand the characters’ emotions a little bit more and in a more mature way. Things like this do happen to kids, so we have to read this book to feel more confident and secure in themselves to confront their own demons” (7tH grader, Speak)

To be balanced, we as English language arts teachers must also remember that ours is a fundamental and Herculean task—instructing and equipping young minds with the necessary lifelong skills from pre-school through high school and undergraduate/workplace: reading, critical inquiry, reflection, perspective, writing, and synthesis/connections, speaking. Ours is decidedly not a profession of proselytizing or politicalizing our students. At the end of every day and every year, each and every student who departs our classrooms must retain individual voice, identity, and perspective. Through reading, discussing, exploring, and expressing themselves about the human condition, writ large through the ages to the present, students experience commonalities, differences, challenges, perseverance, and so much more in the safety of the classroom where their ideas and thoughts and queries should be respected, discussed, and privileged.

This blog aims to walk us all through the process by which we can rethink, reflect on, and then reconsider how all of us—teachers, parents, grandparents, and administrators, can reconstruct safe learning spaces for our kids to learn, inquire, explore, and discover not only in their English language arts classes, but in all of the core content areas and, yes, humanities, as well.

Of course, our first and most critical step is to admit how we must look into ourselves and confront our own preconceptions and misconceptions. We must approach our journey with the single intent being that at the end of the day, what we all want are generations of students who can read, write, think, speak, and process on their own, formulating their own voices, identities, and perspectives through their exposure across the curriculum in English language arts (ELA), mathematics, science, social studies, and humanities.

This blog focuses on ELA not only because it is the area in which John and I work, but also, and most importantly, ELA is the only required course for every student—public, private, and homeschool experience elementary-high school. It is with the ELA classes, as well, that teachers introduce and scaffold the most basic, yet critical life-tools our children will require cradle to grave—writing, expression, interaction, critical thinking, analysis, and connections—all designed to build the necessary skills which promote and formulate life-long literacy.

All of us who cherish and strive to nurture and guide our children to adulthood must always remember and never lose sight of the WHY allowing students to read a variety of texts that support and, on occasion, may be foreign and challenging to what they may experience at home is not only beneficial and critical to becoming a whole individual person, but also why exposure is not always the enemy.

- HOW do we accomplish this re-alignment and, most importantly, sustain the support, re-establish safety, and trust teachers, parents, administrators, and students not only need but require?

While this generation of students continues to astonish me, I must confess that as we work with them, from 4th grade to undergraduate, their keen sense of identity, voice, perspective, their penchant for inquiry and their level of soberness remind me that in contrast, at their age, my schoolmates and I did not experience the emotional and mental “weight” as this generation encounters regularly.

For example, five years ago, as I was leaving a middle school in VA, a boy, a wonderful boy with glasses almost as big as he, walked me out of the building. As we walked, he and I talked about his concern about family finances and how he was trying to figure out he could help his parents; this amazing and wonderful child was a 6th grader. Later, in 2019, as a part of a conference for scholars, a colleague, Dr. Tonya Perry, added as a part of the pre-conference, a field trip to Sidney Lanier High School in Alabama. We met and worked with the students in a large group and individually with smaller groups. The aim of the visit to the high school was to illustrate “what could be,” the possibilities for the students. In the smaller, more intimate groups, we fielded their questions about college as well as their questions about us.

I remember two young ladies quite clearly, even after all this time. One young lady was my designated guide. She was ROTC, and we talked about her plans after high school. Her focus was clear, aspirations high. She unfolded a determined plan to achieve her aims. In contrast, another young lady, just as bright and with potential, presented me with quite a different conversation. This student intended to attend college, but her second question so stopped me in my tracks, and to this moment, I can still see her face and hear her voice: “Can you tell me how I can get out and leave here to go to school? I have to get out of here.”

Among all I have and am continuing to learn and experience about GenZ, I know now to expect the unexpected and to process before I reply. At the same time, I have also learned to observe, listen, pay attention, and above all, be honest and as encouraging as I can.

I cite these two examples out of many to illustrate clearly just how our children are thinking, how they are inquiring, how they are worrying. Often, parents are unaware that this generation of children observe, listen to, and emotionally absorb most of the family dynamic vibes—both good and bad. Juxtaposed to the family is the ever-increasing fear for their own safety. Consequently, parents, teachers, and administrators must now factor in this very critical component: kids today bringing their experiences, concerns, and fears into school with them, including ELA classrooms. This additional dynamic creates a very different learning environment and affects how students interact not only with each other and teachers but also how they engage with texts.

Succinctly, schools, social media, other forms of media writ large, and community comprise environments outside of home in which children interact, communicate, and explore daily. Specifically, in ELA classrooms students can encounter the familiar and unfamiliar through reading fiction and nonfiction texts. Rather than harming them, as some critics are asserting and thereby challenging and banning them, these texts essentially function as vehicles through which students may inquire, reflect, interact with each other from and within the safe spaces of the classroom

- Trust—Parents and Teachers and Students:

- Recognizing our roles and “lanes:”

In the past, both parents and teachers took for granted the trust and care of kids in school, and in English language arts. If a parent had concerns about curriculum or behavior, either the parent could schedule a call or an in-person meeting. My own first encounter with such an issue occurred in my first year of teaching at Irving High School in Texas. To be perfectly honest, I was 21 at the time, confident in my ability to teach, and was supported by an amazing English department and principal.

Shirley Jackson’s short story, “The Lottery,” was at that time not only required reading but also anthologized in all ELA-adopted anthologies around the country. One student and parent challenged my teaching the text because of its violence. I asked my principal, Mr. Hines, if I might literally illustrate to the parent just how I was teaching the short story in class. The only caveat I requested was the parent’s observing in the back of the class and not speaking during the session. The parent would observe, along with Mr. Hines and my department Chair, Ms. Judi Purvis. The class convened, and we continued with the piece. The student whose parent was in the class participated in discussion. What followed I could never have imagined—ever. My 10th graders were not traumatized by the text but were instead inquisitive, posed great questions and made salient points about the characters, the conflict, and outcome. However, it did not end there. Afterwards and still resolute, the parent took his concern to the superintendent, who in turn banned the book in the district, which contributed to the short story’s being banned not only in my class, but in all anthologies in the United States—Texas was and still is the country’s largest purchaser of textbooks. One parent triggered this entire process and outcome.

I cite this one important event because the trust my department, chair, and principal provided me was critical. I even credit the parent’s trust in coming into the classroom to observe. Even if a decision had been made prior to arrival, the parent did appear to be fair. As a result of this nationwide banning of one short story, teachers around the country were urged to send reading lists to parents ahead of the school year in order to build and renew trust and transparency. Even today, these lists typically include title, author, a brief, but concise precis, as well as a list of substitute texts that contained similar thematic threads and structure from which parents could select instead.

Trust.

Both sides must return to our mutual trust for our kids’ sakes. We may not always agree, but the individual actions devoid of any semblance of discourse or exploration or attempts at collaboration harm our kids and strangles the learning process in ways that are both immediate and, more importantly, latent.

“Kids are going to get exposed at some points to these ideas and topics. I think if we can read about stuff like having it in the form of a book encourages people to read.” (7th grader, George)

I always remind myself and tell both graduate students and teachers—parents do not want their children to hurt under any circumstances. They also do not want to be told, “You should read the book” which necessarily implies parents didn’t read—but how do we know?

As English language arts teachers ours is not to rear, proselytize to, or mold our students into what I call “mini-mes.” Instead, what is our primary and critical task: Using fiction and nonfiction texts from around the world not only to enable students to read, write, and think critically, but also to experience, explore, develop and hone a voice and opinion about the thoughts, ideas, actions, reactions, solutions, challenges, and scope of humanity, as depicted by a myriad of authors—past, present, and future.

Our trust with and to parents lies with our ability to remain ever-objective and focused on the literacy tasks at hand for which we alone are responsible. In so many ways and with this generation of students especially, we are both teacher and learner, speaker and listener, guide to and explorer with our students. Consubstantiality with our students or they with us is decidedly not within nor should it be within our purview.

If as English language arts teachers our ultimate aim is to provide each and every student with life-long literacy skills, then our students’ agreeing with us or aligning their thoughts with ours is a non sequitur. Every curriculum in this country today for ELA emphasizes the import of critical thinking, making connections, and honing students’ own voices and point of view.

“I like Morrison [’s] not telling us the races of Twyla and Roberta are great because we can never figure them out by what color they are.” (7th grader “Recitatif”)

- Our willingness “to go there” parents, teachers, administrators: Of all the points in this blog, this one may indeed be the most difficult to achieve because far too often, we have all stopped talking and listening to each other. And the fallout to this non-talking and listening continues to damage, yes, damage our kids’ learning, emotional safety, and sometimes, their physical safety. If we do not stop and redirect so much discord and cacophony engulfing and smothering our kids every single day, the fault will lie with each of us because we will have been the catalysts.

We must re-assume our roles as parents, teachers, administrators whose sole purpose is to educate independent, individual thinkers who can read, write, think, discern, analyze, speak, and connect long after we are gone. We can and must restart and accomplish this task before we lose altogether our children’s’ collective and individual futures.

As Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. foresaw and warned: “The function of education, therefore, is to teach one to think intensively and to think critically. . . . Be careful, teachers!” “The Purpose of Education,” Morehouse College, 1948)

This admonition speaks to ALL of us who care for and love our kids.

This post comes from the TODAY Parenting Team community, where all members are welcome to post and discuss parenting solutions. Learn more and join us! Because we're all in this together.